Why brand architecture matters, and how to get it right

Have you got your house in order? Find out by following our no-nonsense guide to brand architecture, complete with examples of the four most common models

The term brand architecture refers to the way brands are structured, particularly when the company in question is large enough to encompass several products, services or sub-brands.

Without careful consideration, companies like this could end up confusing their customers by presenting a variety of inconsistent (and potentially off-putting) products, marketed at different customer groups.

On the other hand, choosing the right brand architecture can have a positive impact on all areas of a business, allowing companies to scale up and explore new areas of innovation without negatively affecting the perception of existing customers.

The internal and external value of brand architecture

Just as great architecture creates a positive impression on both the inside and the outside of a building, great brand architecture has a positive impact on both internal and external aspects of a company.

When brand architecture is executed well, the internal parts of a business will benefit. Current and future products have space to grow and evolve without getting in each other’s way. Mergers and acquisitions are afforded the space they need to integrate into a wider company strategy, and innovation can take place without sidelining tried-and-tested products that continue to prove successful.

Externally, good brand architecture means that customers, employees and investors can quickly understand what you’re offering as a company. It presents a cohesive and considered image to the world – a brand identity that positively influences people’s perception of your company, and that ties in seamlessly with wider business goals.

Four common brand architecture models

Different companies suit different brand architecture models. Here are the four most common models you’re likely to encounter, along with real-world examples to illustrate how and why they work.

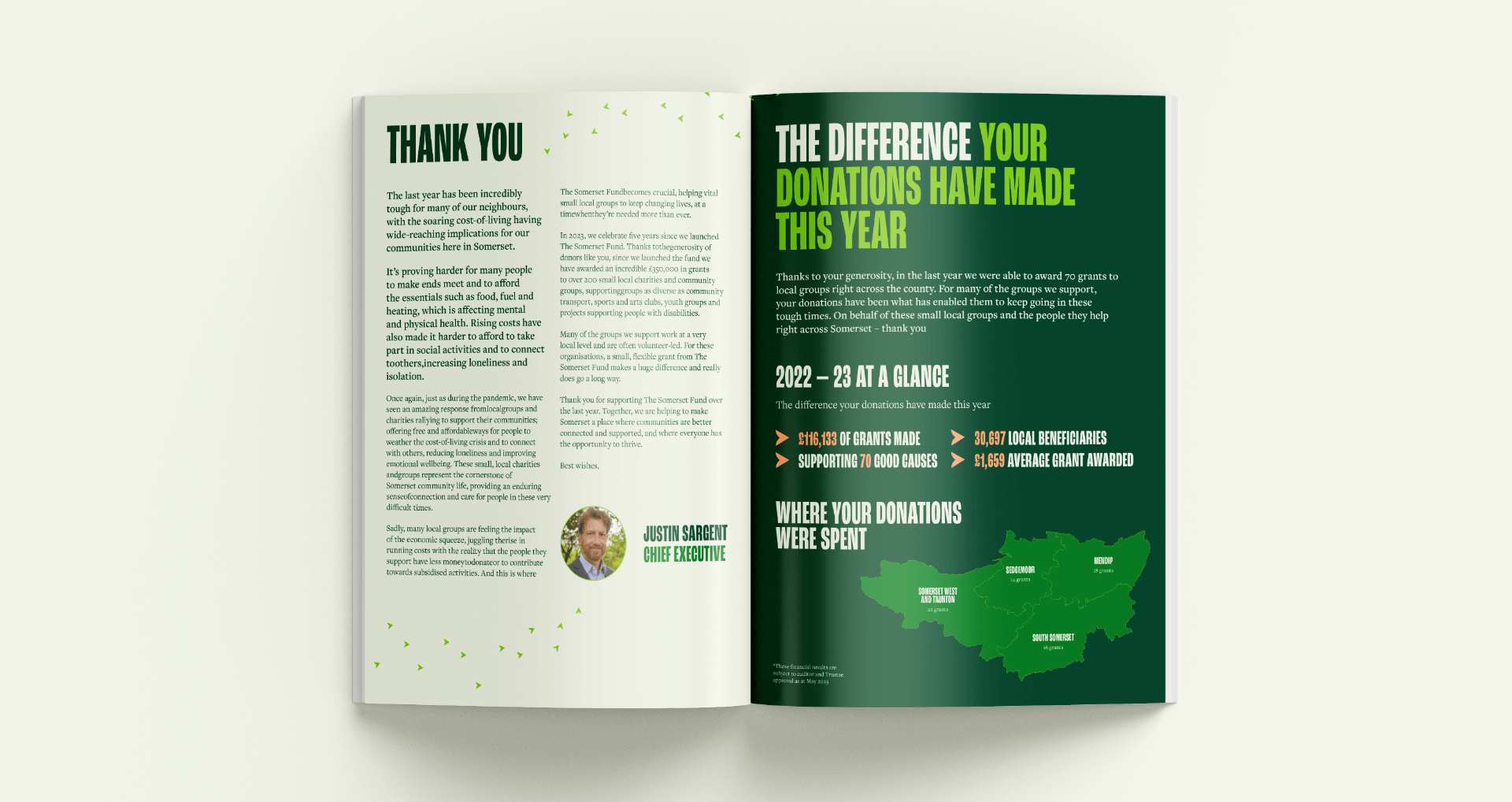

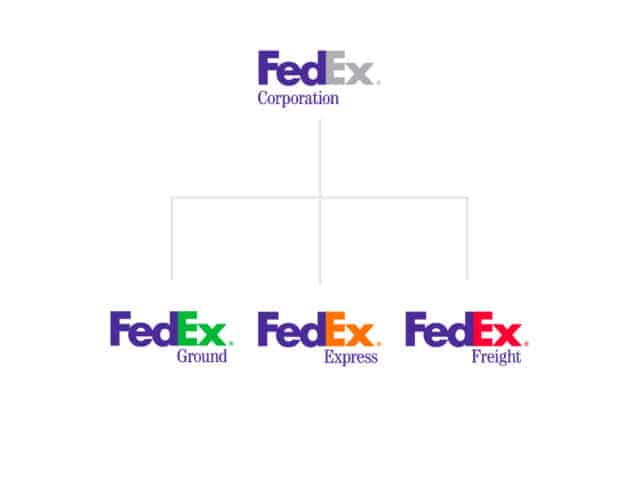

Branded house

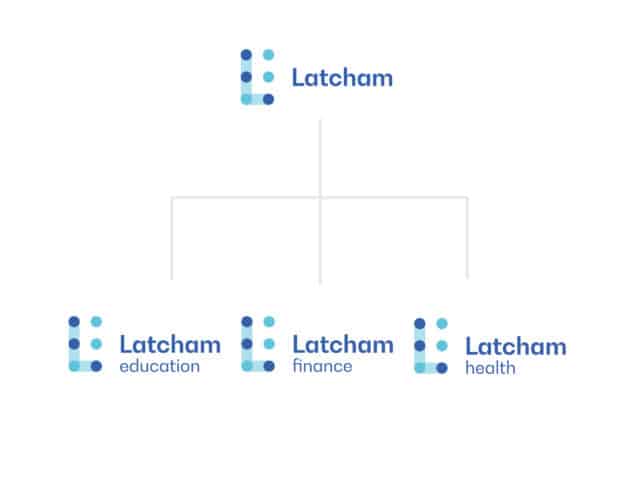

Sometimes known as monolithic brand architecture, the branded house model revolves around a primary ‘master’ brand that leverages its recognisable image to establish a variety of smaller sub-brands or company divisions to serve different markets, sectors or segments.

Examples:

Fed-Ex operates successfully using the branded house model. By using the globally recognised Fed-Ex name as its parent brand, this delivery giant has established a variety of sub-brands to meet the needs of different markets, from overnight airmail (Fed-Ex Express) to a retail-based print and mail service (Fed-Ex Office).

We recently implemented the branded house model with one of our own clients: Latcham, a Bristol-based fulfilment company, wanted to align its brand strategy with its wider business strategy. We quickly realised that a sector-specific family of sub-brands would be an excellent asset for the company’s sales and marketing teams, emphasising the important and advantageous role of sector specialists within the company. This has helped Latcham to build on its already respected brand name with a variety of specialist sub-brands, such as Latcham Health, Latcham Education and Latcham Housing.

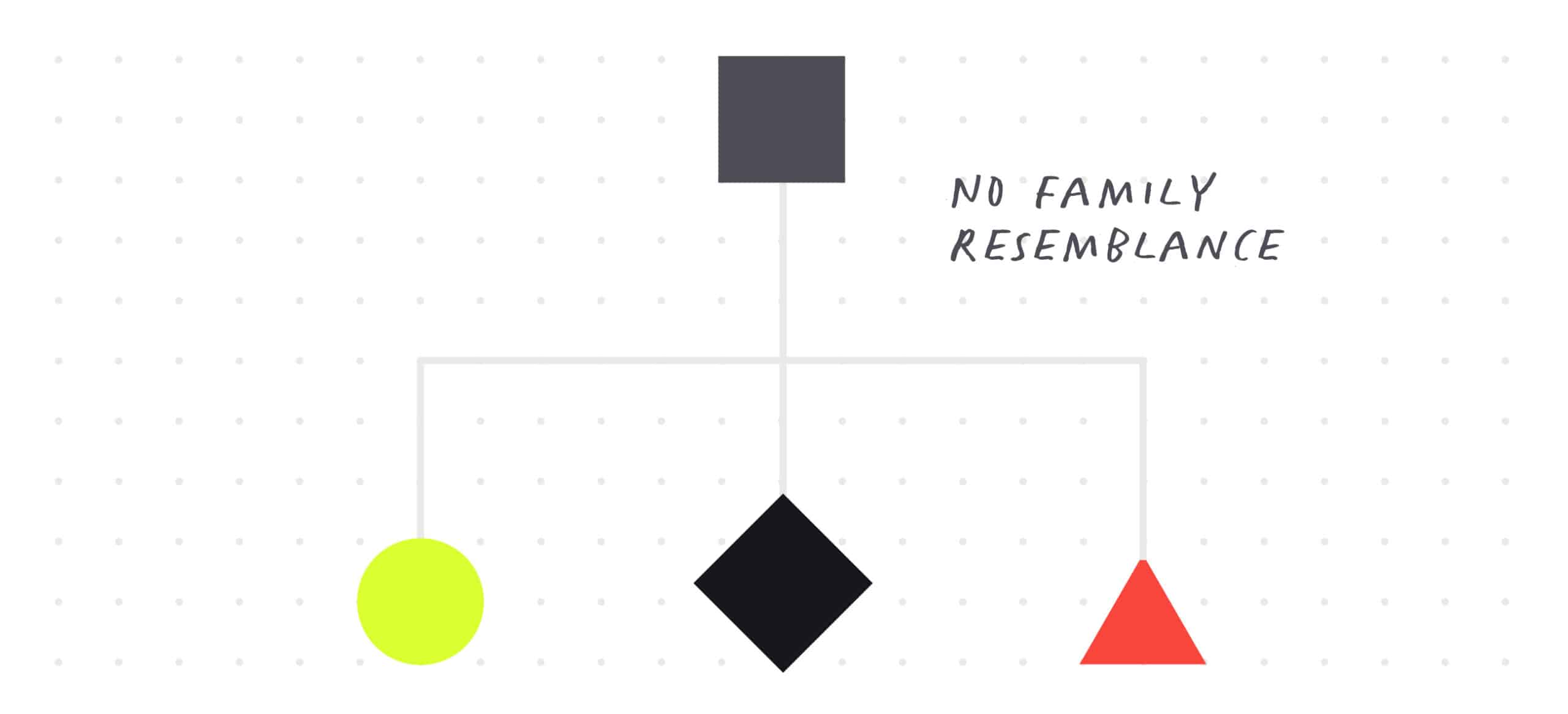

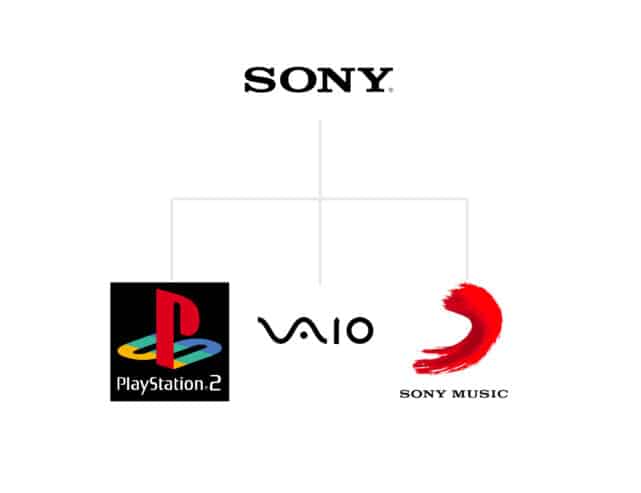

House of brands

In this brand architecture model, there’s no need for the sub-brands of a larger company to bear any resemblance to one another. Indeed, this model suits companies aiming to serve a diverse range of markets or sectors, with a variety of product-specific narratives that don’t always fit neatly into a larger family of brands.

Examples:

As a world-renowned tech company, Sony has a variety of markets that it can potentially serve. It does so by adopting a house of brands model, using a portfolio of recognisable but distinct brands to appeal to different markets, such as PlayStation for gaming and Vaio for personal computers.

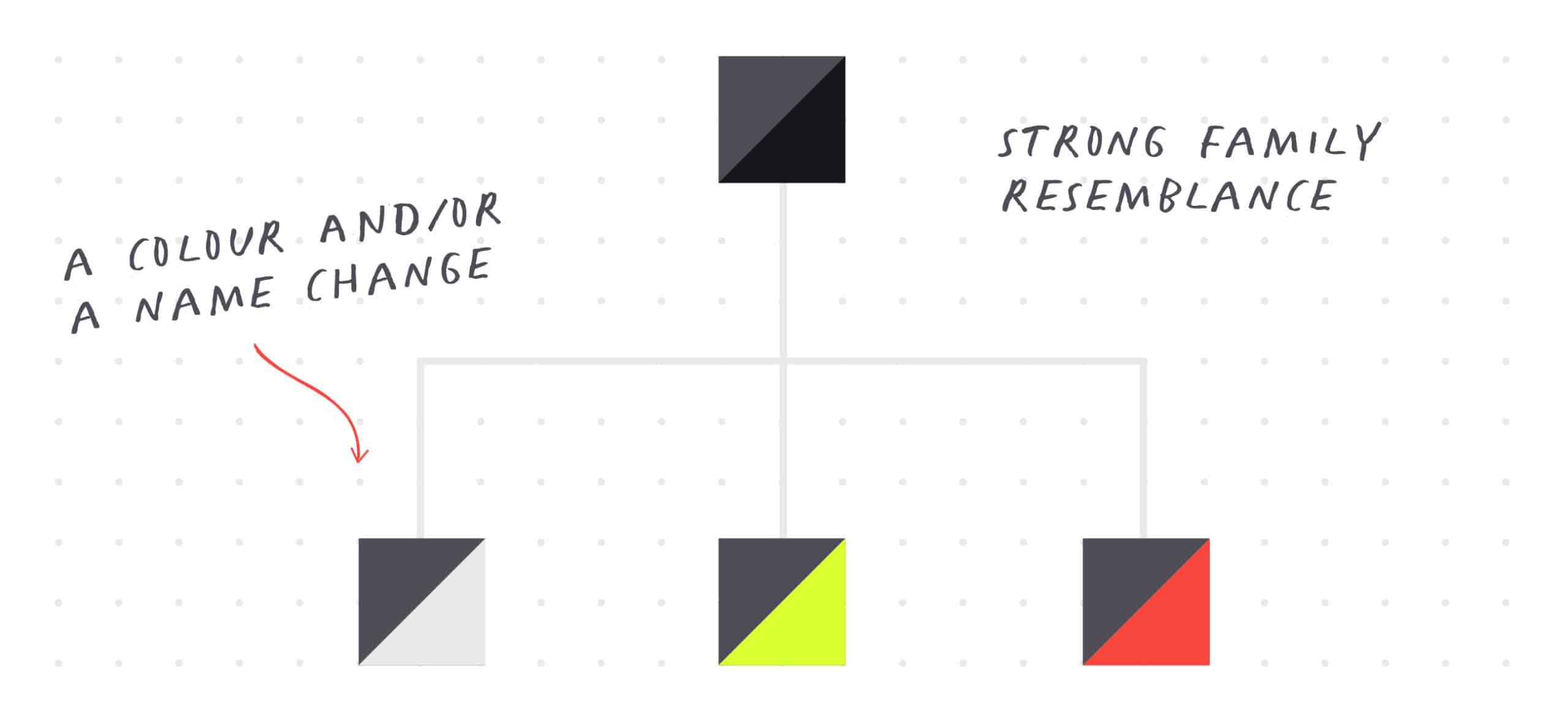

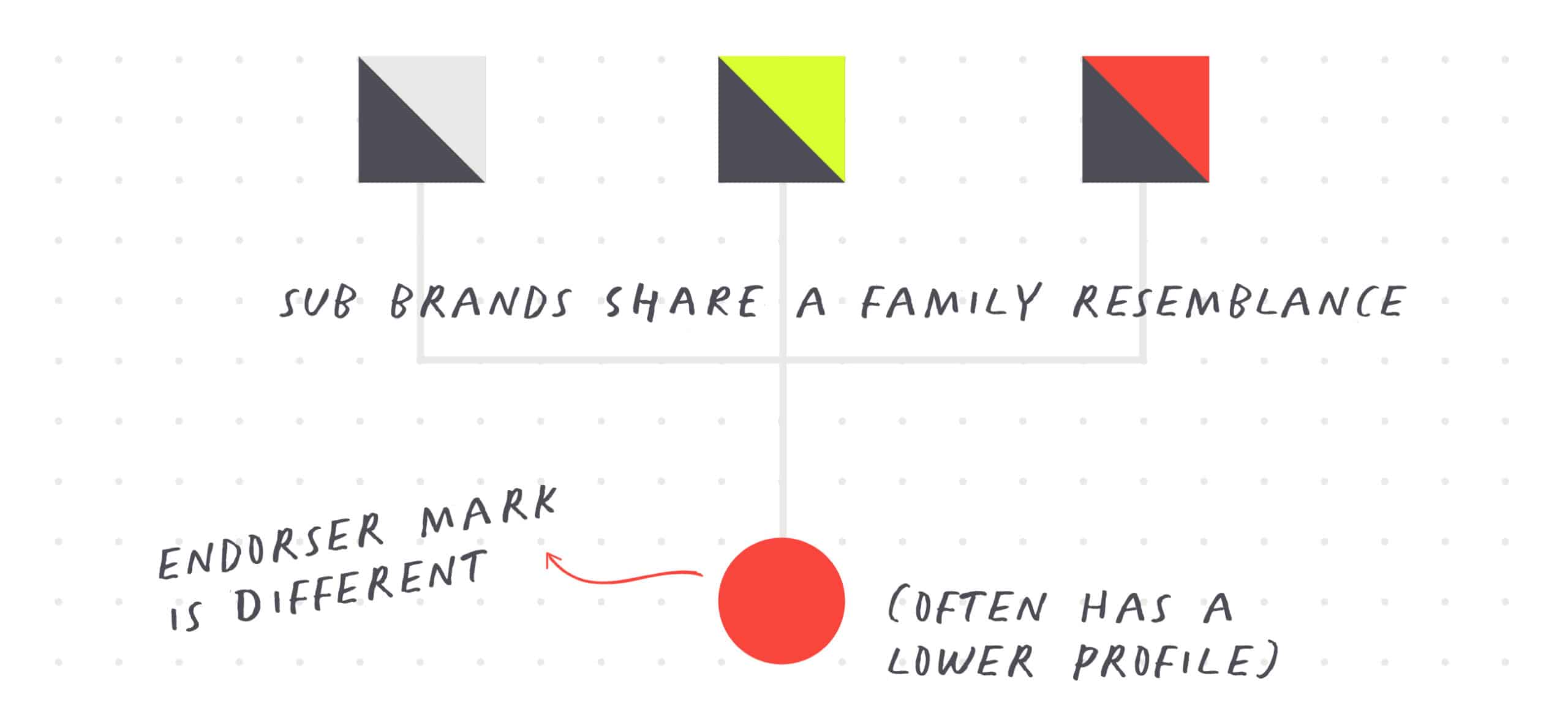

Endorsed brands

Similar to the branded house model, this type of brand architecture relies on the use of a well-known master brand, acting as a mark of consistency and excellence for its associated sub-brands. However, the products or services in an endorsed brand model can look quite different to the parent brand, and may be marketed as individual brands in their own right whilst retaining a family resemblance with each other.

Adobe is a great example of a company that uses the endorsed brand model: its portfolio of software products bear a strong family resemblance, yet use different visual language to the parent brand. However, products like PhotoShop, Illustrator and Premiere each have their own unique offerings; while their association with Adobe helps to make them the industry standard for creative practitioners, their individual differences also allow for more targeted marketing.

We previously used an endorsed brand model when designing the brand architecture for Inside Asia Tours. By creating a signature brandmark and applying it to the company’s different regional identities, we helped the tour operator to successfully endorse and cross-sell its expanding offering of East Asian holidays.

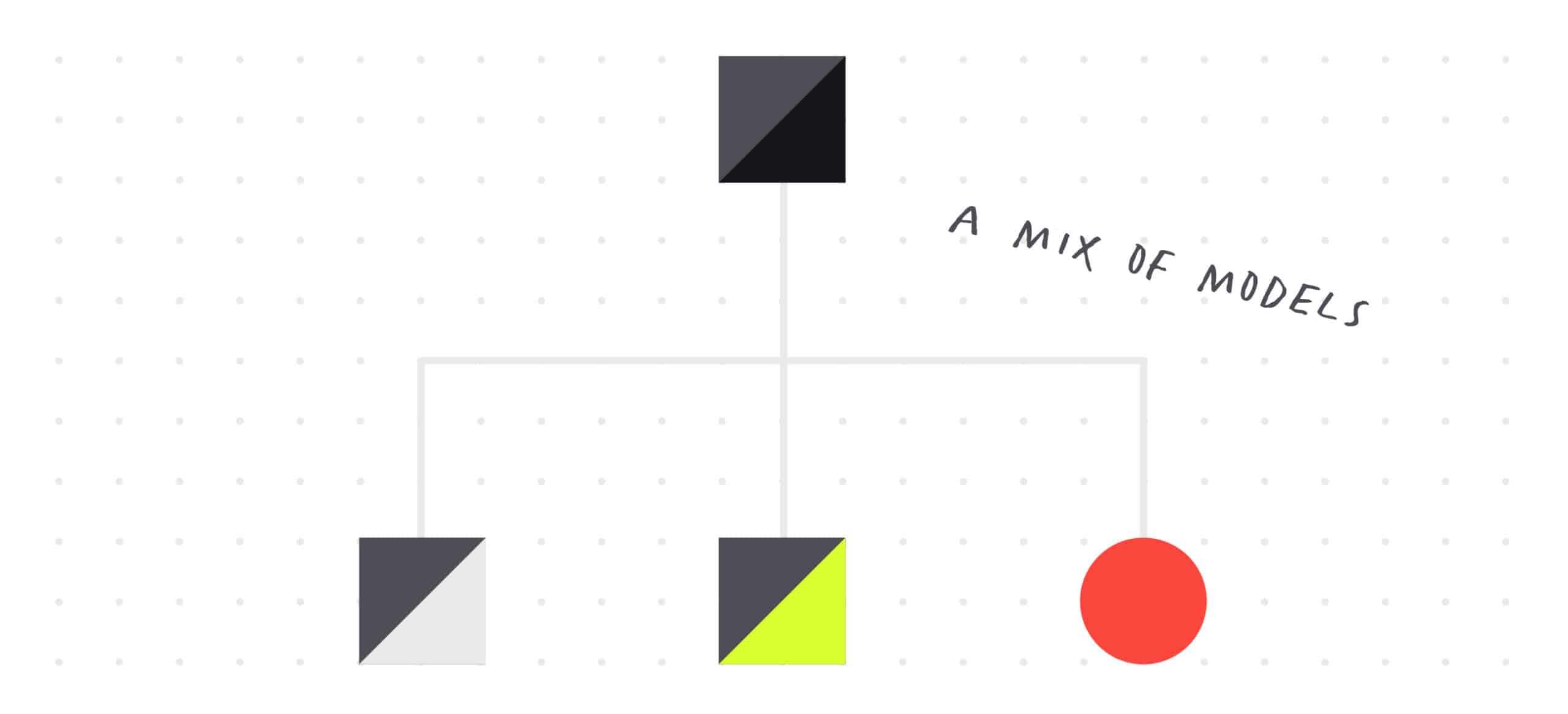

Hybrid house

As its name suggests, the hybrid house model borrows aspects from several other types of brand architecture, allowing for a highly customisable approach. To avoid a confusing and inconsistent narrative around their product portfolios, companies wishing to adopt a hybrid model should plan particularly carefully.

Examples:

Microsoft uses a hybrid brand architecture model to market its wide range of products and services. While some of its software products (like the Microsoft Office suite of programs) bear a family resemblance to the parent brand, other Microsoft products like Xbox and Skype are marketed using their own distinct brand identities.

Adopting a hybrid house model made sense during our work with KTSL, a tech company with a variety of distinct products covering sectors such as artificial intelligence, augmented reality and customer portals. On the surface, KTSL appears to use a branded house model, but it also borrows elements of the endorser brand model, with sub-branded services that can operate independently from the master brand.

Which brand architecture model is right for you?

As you can see from the examples above, different brand architecture models lend themselves to different business scenarios. The model you choose will ultimately depend on your business goals and strategy, as well as the existing structure of your company.

A good place to start is to audit your existing brand. By examining how sub-brands and individual products fit into the structure of your parent company, you’ll be able to assess which brand architecture model fits best with the way your company currently operates. You may then decide to stick with this model, refining it to suit your future goals. Alternatively, you might choose to pivot to a different model that better suits your business’ structure and strategy.

Not sure which model suits your business best? Book a 30-minute call with brand design consultant Sue. She’ll be pleased to help you plan a brand architecture that enables you to build a successful future for your business.